Review: Lazarus #16

And welcome back to our ongoing discussion of Greg Rucka and Michael Lark’s Lazarus.

Although the word “review” is bandied around, this isn’t the place to come for an assessment of whether or not you should buy the book – indeed, if you’re reading this without having read it already, you’re in, at the very least, for some significant spoilers. We aim, instead, to provide an “enhanced” reading experience, touching on details, thematic connections and other areas to read and explore – sometimes with comments from the creators themselves. If you’re keen on further insight into their creative process, you can find our interviews with the creators of Lazarus here, here and here.

As always, spoilers abound for the current issue within! Enough chit-chat! On with the book!

Fiat Lux

“In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth. And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters. And God said, Let there be light: and there was light.”

Genesis 1:1. The creation of the universe.

Worldbuilding.

A concept synonymous with science-fiction and fantasy stories. How does this work? What makes it different? What makes it the same? What makes the characters who they are?

The truth is, every story has worldbuilding. Even roman à clef stories contain shades of it – writers build worlds they cannot wholly recall and observe, even if these are summoned from memory as much as they are from imagination. Every time you tell a tale, you create a universe. We throw the terms out commonly (there’s soon to be a Universal Monster Movie Cinematic Universe, if press is to be believed) and they lose a degree of their currency, but the truth remains that each narrative has the hands of its own little God furrowing at the edges.

Or say rather, little pantheons. They say that the platypus is a duck designed by committee, but if the collaborative nature of comics has taught us anything is that there is no substitute to two, or three, or four creators, on each other’s wavelength, firing on all cylinders. Prose is prose is prose, and a picture may be worth a thousand words, but comics can (and do) draw from the best that visual artists and writers can offer, and also offers the opportunity for new synthesis: place even the most talented artist and the most talented writer on the same project, but if they can’t collaborate you won’t get their finest work.

Most comic teams are bigger than any two contributors, of course. There are unsung heroes, not the least of which are editors, who any creator will tell you can make or break a project depending on their involvement, but also often separate letterers, colourists, in some cases inkers, and so on and so on.

Lazarus includes graphic design, which was what this preamble was gearing up to. It’s time to talk about Eric Trautmann.

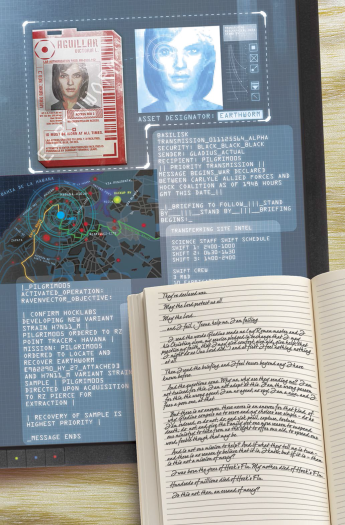

Though the issue credits Greg as writer, it includes the special credit of “artifact pages” by Eric Trautmann and Owen Freeman, and the usual “additional content by” credit for Trautmann as well. Greg’s made no secret of the fact that Eric’s investment in this issue is more significant than perhaps this byline might suggest: all signs point to much of his hand at the wheel.

If you’ve been following Lazarus for a while (as we have) you’ll note that Eric has been responsible for the advertising pages that have drawn acclaim in the back matter, the badges and the little elements of, well, worldbuilding that filter through it. If you’re familiar with his work, you’ll know he’s a gifted comic book writer in his own right as well as a frequent collaborator with Greg. Our interviews with the creative team have included notes about the setting elements Eric has contributed, the backstory and story ideas that he’s brought to the ensemble. He’s also (at times) been a role-playing game designer, building worlds and settings designed to provide interest to players, but to be flexible enough to accept the insertion of a narrative (or narratives) within them, without cracking under the strain.

He’s now joined by Owen Freeman, who has a tradition of employment as a commercial artist, which brings not the traditional storyteller’s skill to these pages (not to say that its lacking) but instead the draftsman’s understanding of layout and artwork that filters into advertising and commercial representation: designed not to “tell” a narrative per se, but to encapsulate and present a thing as real (and in many cases, tactile and obtainable).

Together, they’ve done something remarkable: crafted an epistolary story out of displayed components. The form of an epistolary story – the story-as-found-artifact, ala The Colour Purple, the Last Days of Summer, World War Z or House of Leaves – is certainly common enough in books, but is surprisingly rare in comics. (Pages from the Planet and the Bugle being common exceptions, and League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: Black Dossier springs to mind, but such content is comparatively rare).

Why? It may be the simple lack of people with the skillset to make these sorts of stories, for as this issue makes clear, the requisite labour, knowledge base and eye for detail needed to craft artifacts are higher than the equivalent skill needed to, say, write a novella that looks like a diary or a film that looks like a home video. Even so, the epistolary story is something that comic books seem uniquely adapted to emulate, in that the spread of artifacts available to sample is so wide-ranging. The puzzlemaking of included photographs, the ability to move from image to text and back again, as well as to truly represent by innovative use of panels and space the different texts and items being examined means that comics, more than any medium, can produce the epistolary story to its fullest. Little techniques make that clear – the presence of a tablet computer sitting on a desk for example: the tablet could have simply been produced over white space without changing the content, but the addition of a full wood grained page means that we’re not seeing it in isolation, we’re seeing a deeper, more palpable thing: what the object would look like to us. We see in the same way as the characters.

Comics as a medium are becoming increasingly famous for self-reflection, for analysis of the way in which its stories are told being a function of the stories told. This ever-increasing tendency for comics to be about comics, spread from the smaller ‘indie’ title all the way through to the themes of Big Two events, is laudable insofar as it highlights the power of comics to discuss the interplay between vision and sound, prose and art, but is equally regrettable in that it ignores all the other interfaces between words, sights and sounds. Comics are better placed to discuss our relationships with objects than any other medium. Looked at in this light, the lack of attempts to create this sense of genuine artifact should be startling.

Even though it seems intuitive, this is not to downplay the innovation and flair used by the creative team in putting this issue together. By utilising this format, the issue exalts the question of how the inhabitants of the Lazarus-verse see themselves, and reinforce the external reality of the world. The artifact pages are replete with subtle references and soft world-building that bring you in close to Sister Bernard’s perspective. Lazarus has drawn a good deal of acclaim (not the least in these essays) for the reality of its world, for how concrete (and frighteningly prescient) it seems. To marry that careful worldbuilding with this technique presents something different again, an opportunity for the readers to “live” the experience as much as view it.

This is fairly new ground for comics, despite operating in a medium with a unique sharing of text and image. The issue, however, does not purely stand as an epistolary novel, instead frequently returning to Michael’s evocative art to show the action that Sister Bernard describes. This interplay between the artefact pages and the comic of the Sister’s adventures is complex and magnificent, justifying avoiding the bolder step of going entirely with artifact pages. This is because it allows the paired narratives to bleed into each other, becoming a greater whole. We see the story at once from the outside and the inside. We learn some new things, and we see some old things in a different way. This juxtaposition of experiencing and observing allows us to be part of the world, but to see the order of that world break down from the outside.

We’re viewing an apocalypse as much as Sister Bernard is.

The perfect example of this is the climactic appearance of Joacquim. There is a tension in perspective between what Sister Bernard sees, powerfully expressed through her Biblical imagery, and our prior experience of Joacquim. Diaries and photographs, fictional archaeology, they provide the protection of clinical distance – the sense that after these events, or on some unimagined plane (as we are, looking into, but not part of, the world of Lazarus) – something survives. We are looking at a story: a safe, contained, environment. Joacquim, however, bursts into the present: un-alluded to, unexpected. Our distance from her narrative is shattered, and in so doing, the “world” is plunged into chaos.

This tension would have only been undercut if Joacquim appeared only within photographic stills or “recordings” of combat. And with Joacquim being grounded in the familiar portrayal under Michael’s pen, the connection becomes lasting – Sister Bernard’s perspective of Joacquim will now carry over to his future appearances.

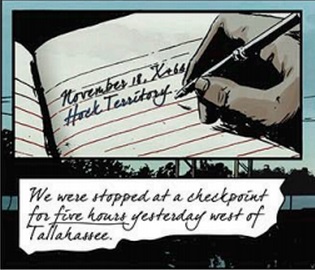

November 18, X+64

This issue grabbed our attention in the first panel of the first page, when our eyes caught this –

Now, in one sense, the use of the date is a confirmation of the nomenclature used before. The timeline added to in the backmatter issue by issue has made this reckoning of time familiar, of course, but presented in the text it creates new issues and questions.

Aesthetically, one must consider whether the structure of marking the date is more compelling in the backmatter than in the setting. In the backmatter, X marks the spot. It stands for the ongoing mystery that the team is spinning for us, a signifier of the joy in the puzzle.

Given Lazarus’ desire to leave the distance between ‘us’ – the readership – and ‘them’ – the future of the comic’s universe – open, it may be in part a convenience and a shield against annotating pedants (…ahem), a way to keep the question of when this all occurs unanswered and unanswerable.

Nonetheless, by moving the terminology in-setting, something equally if not more profound has been unleashed.

It gets repeated time and time again through this issue in the artifact pages, demonstrating that the calendar has been universally overhauled. It is a principle of studying history that the way that people record time tells us about them. The secular calendar of the French Revolution was a defining step in redirecting the county’s self-perception; the gap between Catholic and East Orthodox timekeeping contributed to the split seeming absolute and irrevocable. In the Civilisation video games, the calendar is a key technology, standing alongside writing and the wheel because in genuine anthropology, the ability to divide existence from a timeless hunter-gathering ever-present to a sequence of events – the development of a history – is seek as one of the key markers of emergent human civilisation.

Religious approaches to eschatology, be it the Latter Day Saints or the Aztec succession of ages, frequently involves complicated schedules derived from a sense that calendars are full and accurate representations of objective, cosmological forces.

The power of the calendar, then, helps explain its role in science fiction. We have discussed previously with Greg the growing trend in speculative fiction away from the “rocket ships and cities on the moon” optimism towards doomsday scenarios and visions of total war. Stories around the ‘apocalypse’, a term borrowed from a religious view of the world to indicate the sheer totality of cataclysms of all stripes, often restart the calendar after the fall, to emphasises its profound impact on people’s relationship with history. It plants a flag, saying ‘from here, everything changed for everyone”.

With the Lazarus-verse, planting this flag with the use of “X+”, is suggestive. It demands we approach the mystery of the “X” is a new way, not as a mark of uncertainty but rather of importance – whatever happened in Year X was so exceptional that all time is reckoned by it, and they mark that reckoning front-and-centre, before the year itself. Afterall, 64 A.X, or After X, would be more intuitive if the current year was anywhere near as important than the past event.

This change in perception is emphasised by this being Sister Bernard’s diary. Institutional religious scholarship still prefers to reckon by BC and AD, rather than the increasingly prevalent BCE/CE division, taking as their foundational event the assigned birth year of Christ. To see the church putting aside the centrality of Christ in their own historical accountings to reckon time by the date of their submission to their new secular masters is to immediately and viscerally understand how the world has changed.

The date is thus the microcosm of the issue.

Terrible Swift Sword

The role of faith in politics is central to Issue 16. From a world-building perspectives, this has been a long time coming. Given how Greg has treated the first limb of the old adage of talking politics and religion, consideration of the second was only a matter of time. It ranks high as a question we’ve seen asked of the creative team ever since Lift, and the role of the Pope, of the Middle East, of organised religion in the world after X is surely something that the comic’s very title – Lazarus – invites one to consider.

We’ve drawn a connection before between Hock and Frankenstein (and Malcolm for that matter), the immortal men who play at gods as a metaphor for power and self-aggrandizement, but we have, until now, not spent much time considering what the rise of very human gods means for true believers.

The role of religion in ambitious science fiction is always complicated. To postulate about the future of the world is to make some sort of call about the power and the purpose of religion. Faiths rise and fall over time, but clearly a true faith would not die. Fields of scientific theory and practice are not supported by some religious perspectives, making decisions about the morality, accuracy and efficacy of evolution, biogenetics and quantum physics central to an author’s message.

When talking about the transition from optimistic to apocalyptic speculative fiction, one must note the transition to a vision of the future that often carves out more space for simple faith. When the city on the moon is doomed and no declaration need by made about life on other planets, and the lesson “Man Must Not Play God” writ upon the stars, characters sustained in times of trauma by the strength of their beliefs, move to a more central position. Insofar as apocalyptic fiction paints a picture of our modern, relatively secular, relatively post-modern and anti-tribal social compact as doomed by its greed, ambition and recklessness, it offers a conservative vision of the future owned by those with humble approach to the ineffable and a return to family values.

But, of course, this vision is too simplistic, both in its positioning of faith as inherently reactionary, incurious and tribal, and its picture of the technocratic futurism as something legitimately pro-science or pro-tolerance. Lazarus does much interesting work this month in undercutting that simplicity and respectfully painting the picture in its full complexity.

Lazarus paints itself – or at least the Americas – as a place of diminished religious influence. Statist powers push a technocratic vision that gives little breathing space. In Lazarus, the sheer weight of biotechnology readily applied, genetic testing and screening and enhancement, betokens a degree of comfort with tampering with and mapping the genetic makeup of humanity that must have formed a stumbling block for any hardline church. It’s easy to imagine fanatical Catholics burning themselves alive before allowing teratogenic changes, mosques being bulldozed for refusing to accept polluted water supplies, angry riots by which faith healers fought back against perceived technological demons.

Nonetheless, Greg has avoided the easy road of painting religion in terms either of critical disdain for a reactionary force or supportive paean to a simpler, more pure way of living. Instead, the story embraces the complexity of the role of religion – and its lack – in the human experience. Issue #16 paints the struggling faithful nuns as a highly educated, scientifically progressive, socially liberal force of compassion. It draws parallels between the reactionary Stalinist approach to science, with Lysenkoism and forced secularisation, and the backwards, superstitious and prejudiced Hock technocracy, suffering as it does from the state religion of Peter Hock and the influence of a very literal “opium of the masses”. It considers the historically essentially positive relationship between the disposed and their faith in the context of a narrative highly critical of class distinction.

Above all else, accountability and faith are the critical questions that Lazarus #16 grapples with. Losing her faith in God, Sister Bernard still chooses to lay down her life for her fellow man. At the moment her sacrifice seems meaningless, Sister Bernard’s journey takes her to a place where she loses her faith completely…and then regains it in a terrifying, galvanising instant. When all hope is lost, a wrathful angel appears from on high, and saves her.

The sister’s compelling inner struggle, brought to life by the epistolary format, makes us, whatever our backgrounds, ask the questions she wrestles with – how does God survive when nations have collapsed? When the state demands everything? When the centrality of your faith is eclipsed by something other? Her answer – though not necessarily her final answer, as I hope we’ll see her again – is terrifying. Though this is not the first time we’ve compared Neon Genesis Evalgellion with Lazarus, it is certainly the most compelling. When the faith of a woman trained in biomedical science can be restored by a vision of “The Wrath of God”, a technological accomplishment broadly in her field, one must wonder just what has been created, and whether the hands of man can truly control such a force.

Again justifying the return to Michael’s art, the closing pages of the issue certainly make us feel Sister Bernard’s faith return to her. Having lost everything, a smiling man brings her from her knees to her feet, tells her he will make her safe under the golden perfection of a Santi Arcas sunrise. It is presented as a miracle. But miracles can be complicated things…

There but for the Grace of God

Just as the recording of the year both told us something about the world and helped introduce the central tension in Sister Bernard’s story, so too does each further artifact page draw out the tension between her secular and religious roles, and the collapse of the clear divides with which the institution of the Church sought to make its role and its adherents lives make sense.

The strict division between Church and State (…render unto Caesar that which is Caesar’s…) is breaking down as Caesar moves to demand the full efforts and attention of the whole world. There is no time for scruple now.

The tension between the desire to do the “right thing” and the need to dirty your hands doing it is actually a traditional point of tension for stories about figures of the cloth. The Catholic novels of Graham Greene (particularly The Power and the Glory in which a Catholic priest seeks to avoid arrest and practice a compromised version of his faith in a state of violent totalitarian upheaval) focus on this question to a large degree: can circumstances allow you to be a person of faith, where the circumstances render that faith at best ironic and at worst monstrous? If everyone is martyred for the cause by refusing to comply with directives, who will be left to preserve and promote any kind of good? Can a bad representative really carry the flame when brighter lights have guttered out, or is something inevitably lost when compromises are demanded?

These aren’t easy questions to answer, but they share an issue with another kind of story: the spy story. Only faintly glimmering in James Bond, these issues reach their apotheosis in novels of the John LeCarre ilk, where agents grapple with these questions of who they are and what purpose they serve. The preservation of the State, which once seemed like a moral good, may require too many compromises: a question for the agent of ideals as gripping as any tension over the cruelty of an absent God.

These are not new connections or tensions to draw. Graham Greene, whose Catholic novels we referred to above, was also a prolific author of tradecraft stories in this mold, thrillers that nevertheless beg these questions: what are we striving for, in the darkest nights of the human soul?

Where Lazarus differs from these stories is in the insertion of the apocalyptic, the element where James Bond and his ilk often diverge from the quiet, desperate realism of more realist stories about spies.

“It’s the end of the world” is a refrain in the high-pop thriller: if the mad tyrant gets their hands on the doomsday device, it’s game over unless our hero can stop them. Dismissed as the stuff of fantasy, abstracted from realpolitik into secret games of cops-and-robbers, these stories nevertheless contain the highest of stakes. We accept spies and informants in these stories not as grubby denizens of small gains, but as heroes paying any price to keep us alive.

Note Sister Bernard’s callsign: Pilgrim005, referencing both her role as a religious traveler, but also echoing her status as a double-0, a Nightingale. Her handler, Gladius, conjures both the immense civil power of the Roman Empire, but also the credence of living by (and dying by) the sword. The artifact pages refer to Basilisk transmission, used to transmitting imagery – reminiscent of the idea of Basilisk hacks, the sf conceit where images can enter and reprogram the human brain much as the mythical basilisk turns men to stone through site alone.

Perhaps the most “super-spy” of the constituent elements is the deployment of an apocalyptic virus, the dirty war nightmare that replaced the nuke as the world-ending bogeyman on the 21st century. At once, it is an unstoppable doomsday weapon, deployed by an impossibly ancient, super-scientifically enhanced scientist with a spooky sounding name (say “Doctor Hock you’re totally mad” in your best Connery impression, we dare you) and a frighteningly plausible possibility when you consider how close we’ve come to losing control of our man-made grim reapers time and again.

Like the scenario, Sister Bernard herself is at once the realist spy and the hyper-real spy. Again, the question is why? What purpose does it serve in the broader narrative to place her so?

One of these things…

is not like the others.

The heart of the distinction between threads of spy narrative is the approach to the status quo. In all breeds of story, the spy is the defender of the status quo. In hero-spy stories, this is because, however dark the spy sheltering society is, the status quo is unarguable good, especially compared with the terrible designs of the villain pursuing their new world order. In darker tales, the defence of the status quo is presented more cynically – firstly, the spy is defending a system that is corrupt, reactionary, classist and selfish, and secondly, the spy defends those aims ineffectually, with victories often painted as transitory, pyrrhic and not worth the cost. Spy games are exactly that – games, with little capacity to change the historic trends that buffet people this way and that. The only beneficiaries are the bastards in Whitehall, and usually at the expense of their constituents.

Lazarus blends these visions together, seeking a place of equipoise. Exemplars of objective good and evil are sparse on the ground, and the status quo is utterly horrific. Nonetheless, Lazarus seems to accept the value of service to a greater good. With Sister Bernard’s mission, she accepts after long contemplation not because of loyalty to the Carlyles or to protect herself, but because the stakes she fights for are so clear and so high. For her reward, the actions of the individual are painted as costly, perhaps even unto the cost of their soul, but not ultimately futile or necessarily only for the benefit of the bastards.

The selection of partially submerged Havana (not the least drawing another Graham Greene connection) captures this balancing act wonderfully. The setting is a classic Cold War staple, haunted by Castro, the Cuban Missile Crisis and a legacy of ineffectual bastardry, but here, he soft world-building highlights the way in which the place has changed. Formerly communist Cuba is now a Hock territory, fallen alongside every nation has fallen in the previous reordering of the world. The partially submerged city patrolled by shallow water vessels is one of the first formal nods to global warming. This is a world where things beyond what the rulers call themselves do change, and generally for the worse, where good people do not do enough to stop it.

It is a world that is frighteningly familiar, and one from which no-one can escape accountability.

Dulce Et Decorum Est, Pro Patria Morray

Yes, it’s doggerel Latin, but who can resist a pun? November 18, by the way, is the date of the end of the first Battle of the Somme, Wilfred Owen fans, if anyone’s counting – though it’s likely a coincidence, and not a reference.

The Morrays appear at the end, a very literal deus ex machina (for who could be more god and machine than Joacquim?). But is he there to save her? Recent issues have hinted at the instability of the Morray-Carlyle alliance, of the Morray’s defecting to the paved-over pastures of the Hock camp (and don’t it always seem to go, that you don’t know what you’ve got ‘til it’s gone?)

While David finds Joacquim far too dreamy to ever think wrong of him, Robert continues to side-eye Joacquim, as he has ever since Issue #13. It would, he argues, certainly be consistent with Joacquim’s relationship with Forever in Issue #13 if the Morrays have changed allegiances; keeping his enemies close, the smiling assassin accomplishes his goals with the charm offensive. If Sister Bernard is to be treated as the 00 Agent of our superspy story, than Joacquim Morray certainly makes a more than adequate “Bernard Boy”, the rescuing seducer who betrays our heroine before the final reel.

Or have the rumours of Morray’s defection been exaggerated? Hock propaganda still refers to the “fattening pens of Morray’s famine-driven cannibalism”, drawing a link between Catholics and cannibalism which goes back as far as Christianity itself. Can any relationship be repaired after that much vitriol? Is Hock’s docile population so drug addled as to accept that they have always been allies with Eurasia, even where Eurasia are the flesh-eating maniacs of yesterday?

Is it all an elaborate triple-bluff? Or does Hock’s world of total war cross a moral line that the Morrays wouldn’t follow him over? Has, in fact, the golden rule of morality (potentially backed by faith), won out?

We know war was declared, but because of where we left Conclave we don’t even know who the sides are. We are confused, cut adrift, discombobulated, left to scramble for answers in a world sliding into chaos. Left to try and hold on to something to make sense of the atrocities, to hope that everything might turn out alright. We’re a lot like Sister Bernard in that.

Unlike Sister Bernard, though, we know that next month, Lazarus and the Lazari will return to the forefront – that we can see the arc of the universe, or as much of it as the next sliver of the story provides us. We are being taken on a journey, but the forces are not outside our control. We can close the book, put it down on the table, and look elsewhere if we choose.

Except, as we keep saying, the questions Lazarus poses aren’t going away. We can shut our eyes to them, or trust in faith to answer them, but they’re with us whether we’re reading or not. We’re trapped in the arc of a universe we can’t fully comprehend or understand, struggling to find meaning.

April 22, 2015

I am once again blown away by the depth of your investigation into what we’re doing, gents.

(For the record, I’ve been trying to do something like this in comics for years; Greg and I came a hair’s breadth away from doing it in Action Comics, with excerpts from a Kryptonian bible, but that got blown apart by production issues, alas.)

Thanks!

April 22, 2015

You are more than welcome!