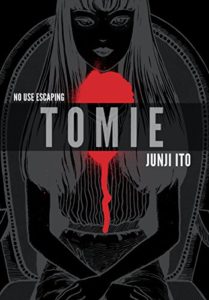

Junji Ito wrote the creepiest comic book that I have ever read–Gyo–so it was with some excitement and trepidation that I opened the phone-book sized Tomie: Complete Deluxe Edition, and it did indeed have not only the gravity of its material weight, it also was drenched in the gravitas that resulted from Ito’s witches’ brew of the horrific and the banal. However, the horror in Tomie was a quick-acting agent to which I quickly became inured after being saturated with the formula.

Like Gyo, part of Ito’s formula in Tomie is to begin with scenes and settings that are ubiquitous in daily life, that are so overexposed as to become banal, such as apartment buildings and schools; additionally, some of the more chilling moments occur in connection with everyday items–Tomie’s photos show a twinned ghast head, so that she’s literally two-faced, or Tomie’s blood saturates a carpet swath, to grow a half-dozen Tomie heads like so many potted plants. Later, Ito experiments with a more gothic mood when Tomie visits a castle-like manor, but by then we already know Tomie as a horror that we have let in to our day to day lives, so that we’ll never see a carpet or a yearbook photo without remembering Tomie.

Tomie is a murder-muse, that inspires her charmed men to slay her, so that her spore-like remains can pollute the Earth with even more Tomies–all of which are pricked by a sororicidal desire to kill their clone sisters. So blood, death, and murder are the primary content of Tomie, and it grows to become gratuitous, to make the reader feel genre ennui when its read, not in its intended serial format, but as a compendium of Tomie’s abominations. While it could be read in one sitting, having done that myself, I’d recommend taking it slow, so its effect isn’t numbed.

One of the best things about a comic or manga in which the writer and artist are the same person is that the writing is either subordinated to the art, or better yet, sublimated by the art process. The mangaka has no need for lengthy exposition, and doesn’t need to debase his or her characters by using them as mouthpieces, as he or she can take as many pages as necessary to convey their points visually. This is especially effective in Tomie, in which the cast of characters is particularly degraded, and none of them have any need for monologuing their shallow, sordid, desires. That said, Ito makes excellent use of dialogue by contrasting it with his gifts with light, shadow, and the spareness of his line, to unnerve the reader.

However, there is a sense of haste in Tomie that isn’t present in the much more decompressed Gyo, and whether this is due to the former being the first work of an author not yet in his prime, or whether it is due to the serial format of its release, the result is that Tomie stories cram too much shock in their twenty to thirty pages, that would be more suspenseful in a longer, more restrained format.

Yet I can’t deny that Tomie has left her undying effect on me, and I can understand why these tales have gone on to inspire an eight movie cinematic franchise in Japan. She’s an inspired horror villain, deserving of a novel-length treatment, and though it may be unlikely that Ito will return to the creation of his youth to write her definitive story, perhaps Tomie will find herself in some other medium.

The Complete Tomie was released on December 20th, and if you find it sold out, you can order it in print or digitally through Viz.

Viz Media sent the review copy.